Key Takeaways

- De-escalate when a situation starts getting tense—be clear that your goal isn’t to argue.

- Ask questions aimed at discovering more about a person’s issues—even if you’re sure you already know everything.

- Try to identify overlap between your interests and the other person’s—so you can both see how working together will get each of you what you want.

Being successful often requires taking definitive stands and sticking to them, in our experience. This can happen if you’re an entrepreneur who has crafted a new vision for the future of your company. It can happen if you’re a corporate executive leading a division of people toward a major goal. And it can happen if you’re a parent trying to get a surly son or daughter to take any number of actions.

The challenge, quite often, is that you need to get results—that is what makes you successful, after all—in the face of pushback. When you’re met with resistance, arguing with others rarely translates into the results you are looking for. But if you take a page from highly successful people, it may be possible to turn arguments into discussions that are both meaningful and productive. These types of discussions can lead to you getting other people to work with you more cooperatively and effectively—with less fighting and stress along the way.

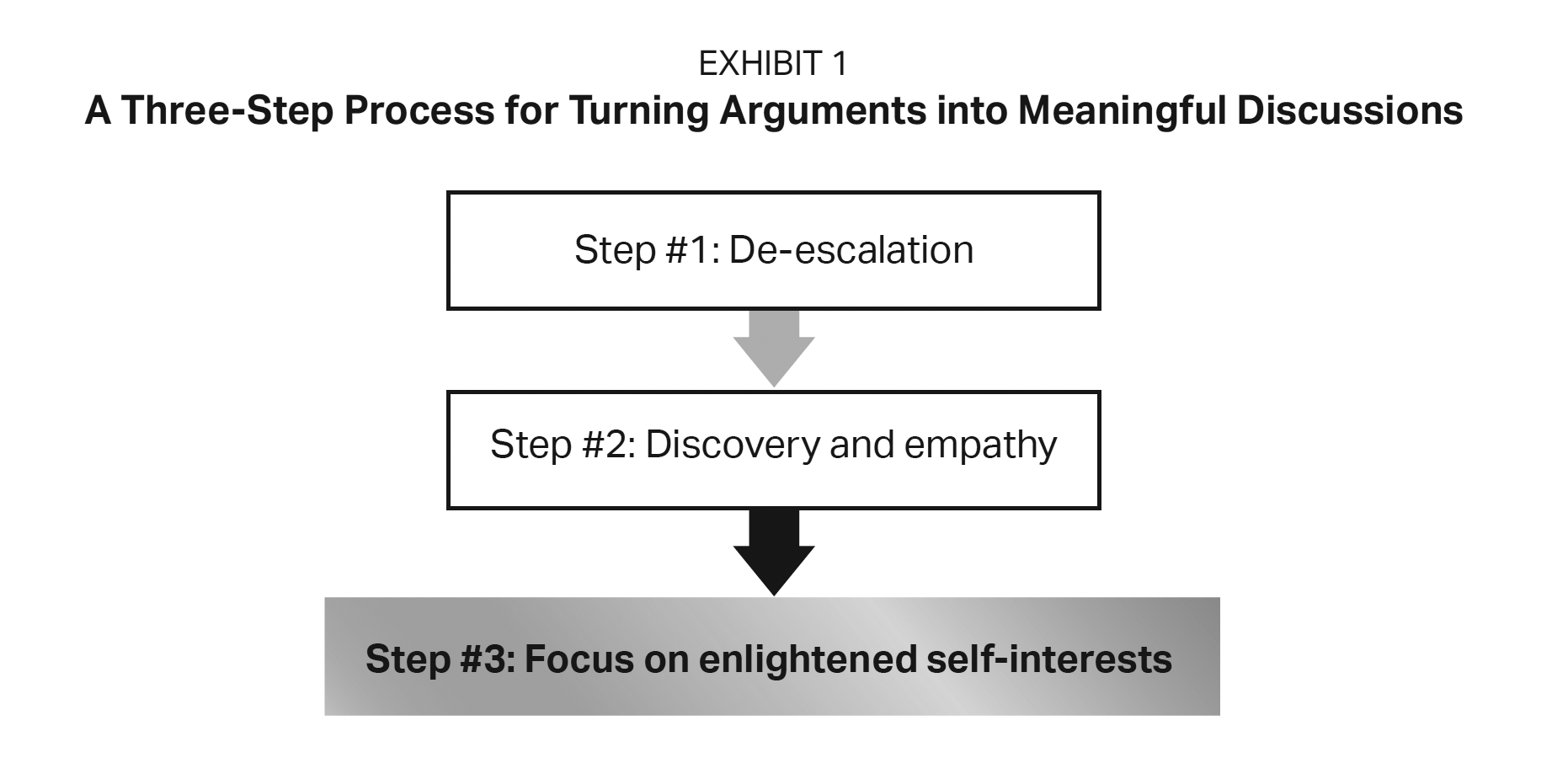

Three key steps

One systematic, repeatable process to turning arguments into discussions that we see used by many successful people is summarized in Exhibit 1. The starting point is de-escalation, followed by discovery and empathy, and then a focus on the enlightened self-interests you share.

Step #1: De-escalation

When a situation, discussion or environment starts to become tense, you want to quickly and powerfully convey that you are not interested in fighting. An easy way to do this is to make one of the following statements:

- “I’m not here to have an argument.”

- “I’m not here to fight with you.”

- “I’m not here for a competition.”

The reason to de-escalate is to sincerely show that your goal is to avoid arguing. You recognize that there is usually no way to get the results you are looking for if there is too much conflict. When things escalate, people get more emotional and their positions (which you disagree with) tend to solidify even more.

Another way to de-escalate a situation, and keep it that way, is to make sure you don’t talk over the other person—as doing so conveys that you don’t really care what they have to say. Also, try not to raise your voice or speak too quickly.

If the discussion does start to get heated and appears to be turning into an argument, you can always lower the temperature by slowing things down. Take more time before answering a question or making a statement. Rapid-fire back-and-forth commonly contributes to fostering disagreements and tension.

Step #2: Discovery and empathy

You might believe that you understand the other person’s point of view—their positions and rationale. And you might be accurate. Nevertheless, it’s often smart to be “professionally ignorant.” This means going into the discussion as though you know little or nothing in order to discover the facts.

There are two main reasons for being professionally ignorant:

- You want to confirm that you understand the other person’s thinking as well as the premise and logic behind that person’s positions. The best (and sometimes the only) way to get this information is directly from the person. Doing so also makes sure you are dealing with that individual and not with other people who have similar positions.

- You want to make sure the other person knows that you understand their viewpoints and what that individual sees as support for those views. Until the other person truly believes you really understand those views, you cannot have a meaningful discussion. Instead, you might often hear the refrain: “You just don’t understand.”

Discovery is how you confirm your understanding. Empathy is how you show it.

In a discovery process, you commonly employ open-ended questions to elicit information. You want to find out as much as you can about someone’s thought processes and conclusions. Some questions that can be useful include:

- “Where did you get that information?”

- “How did you come to those conclusions?”

- “How confident are you that this information is accurate?”

Don’t be critical or confrontational when asking these types of questions. Instead, communicate that you are seriously trying to understand the ideas and viewpoints of the other person.

You will likely want to dig deeper into the responses the other person initially gives you, as it can be very helpful to get extensive answers. This can be easily accomplished with an open-ended question such as “Can you tell me more about that?”

While discovery is how you learn and grasp someone else’s worldview, empathy is how you communicate to that person that you actually grasp that worldview. You can think of your empathetic responses as trial balloons—ways of confirming whether you are on the right track. Empathy helps reduce errors and misperceptions.

Important: Empathy is not just parroting back what someone said. You’ll get a more positive reaction if you distill someone’s core messages into your own words and then see whether your summary is accurate. Sometimes your empathetic responses will be short and pithy; other times they might be long summaries. Many of the best empathetic responses include both what someone believes and the reasoning for that belief.

Also, being empathetic does not mean you have to agree with the other person. In a scenario in which two people are coming from two different places, you likely do not agree. Instead, empathy simply means showing the other person you really do understand where they are coming from. This way, you can never be accused of ignorance or stupidity—which are all-too-common conclusions in arguments.

Step #3: Focus on enlightened self-interests

In some situations, your beliefs are not going to change—nor are the other person’s beliefs. It is just not going to happen in either direction. In these situations, all attempts to win over the other person are exercises with very high probabilities of failure.

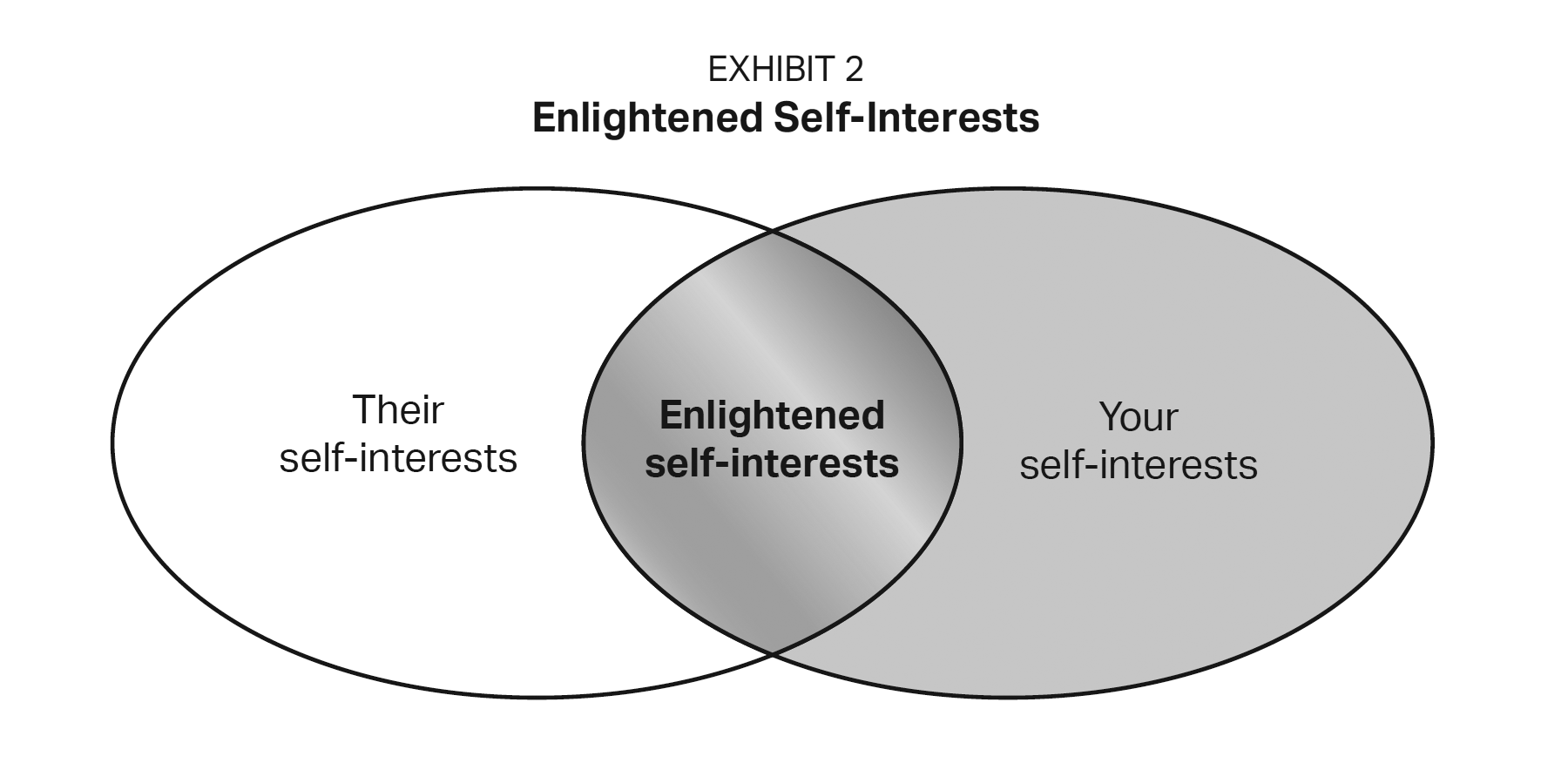

That’s when a fundamentally different approach can make all the difference. You need to appeal to the other person’s self-interests that overlap with your own self-interests. This is referred to as enlightened self-interests (see Exhibit 2). It can help turn a potential argument into a discussion about the possibility of mutually beneficial courses of action.

The more overlap you can find between what you want and what the other person wants—and the more it is that your respective actions can further your shared goals—the easier it can be to actually reach agreements.

The power of this approach stems from the fact that when you appeal to people’s self-interests, you are not trying to change their minds. It’s not persuasion or some type of sales strategy. Through your discovery process, you have likely unearthed areas of overlap between yourself and the other person. That enables you to accentuate the areas where you have some level of agreement and concentrate on the opportunities and possibilities that actually do exist.

Of course, there will likely be areas where you strongly disagree with the other person. There are likely going to be times when you will confidently need to stand by your positions. But even at these times, it is important not to come across as confrontational. An effective way to do this is with the following statement:

“Yes, _________, but _________.”

Here, you highlight where you agree (“Yes, _________,”). Then you cite where you do not agree (“but _________.”). Again, the emphasis is on areas of agreement.

Conclusion

Ultimately, finding common ground is often so important in achieving success—even with people with whom it first appears there is no common ground. It’s all too easy to argue, to disagree, and to support and defend a position without a willingness to budge. It can be much harder to find ways to work together.

0 Comments